Why Soccer Matters Read online

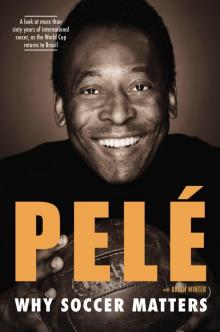

PELÉ

with BRIAN WINTER

WHY SOCCER MATTERS

A CELEBRA BOOK

Celebra

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Celebra,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) LLC

Copyright © Sport Licensing International, 2014

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

CELEBRA and logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA:

Pelé, 1940–

Why soccer matters/Pelé ; with Brian Winter.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-698-15005-8

1. Pelé, 1940– 2. Pelé, 1940—Travel. 3. Soccer—History.

4. World Cup (Soccer)—History. 5. Soccer—Social aspects.

6. Soccer players—Brazil—Biography. I. Winter, Brian. II. Title.

GV942.7.P42A3 2014

796.334—dc23 2013043730

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Version_1

Contents

Title page

Copyright page

Dedication

Introduction

BRAZIL, 1950

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

SWEDEN, 1958

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

MEXICO, 1970

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

USA, 1994

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

BRAZIL, 2014

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Acknowledgments

For Dona Celeste, with much love

Introduction

I close my eyes, and I can still see my first soccer ball.

Really, it was just a bunch of socks tied together. My friends and I would “borrow” them from our neighbors’ clotheslines, and kick our “ball” around for hours at a time. We’d race through the streets, screaming and laughing, battling for hours on end until the sun finally went down. As you might imagine, some people in the neighborhood weren’t too happy with us! But we were crazy for soccer, and too poor to afford anything else. Anyhow, the socks always made it back to their rightful owner, perhaps a bit dirtier than we originally found them.

In later years, I’d practice using a grapefruit, or a couple of old dishrags wadded together, or even bits of trash. It wasn’t until I was nearly a teenager that we started playing with “real” balls. When I played in my first World Cup, when I was seventeen years old in 1958, we used a simple, stitched leather ball—but even that seems like a relic now. After all, the sport has changed so much. In 1958, Brazilians had to wait for up to a month if they wanted to see newsreel footage in theaters of the championship final between Brazil and the host team, Sweden. By contrast, during the last World Cup, in 2010 in South Africa, some 3.2 billion people—or about half the planet’s population—tuned in live on television or the Internet to watch the final between Spain and the Netherlands. I guess it’s no coincidence that the balls players use today are sleek, synthetic, multicolored orbs that are tested in wind tunnels to make sure they spin properly. To me, they look more like alien spaceships than something you’d actually try to kick.

I think about all these changes, and I say to myself: Man, I’m old! But I also marvel at how the world has evolved—largely for the better—over the last seven decades. How did a poor black boy from rural Brazil, who grew up kicking wadded-up socks and bits of trash around dusty streets, come to be at the center of a global phenomenon watched by billions of people around the world?

In this book, I try to describe some of the awesome changes and events that made my journey possible. I also talk about how soccer has helped make the world a somewhat better place during my lifetime, by bringing communities together and giving disadvantaged kids like myself a sense of purpose and pride. This isn’t a conventional autobiography or memoir—not everything that ever happened to me is contained in these pages. Instead, I’ve tried to tell the overlapping stories of how I’ve evolved as a person and a player, and a bit about how soccer and the world evolved as well. I’ve done so by focusing on five different World Cups, starting with the 1950 Cup that Brazil hosted when I was just a small kid, and ending with the event that Brazil will proudly host once again in 2014. For different reasons, these tournaments have been milestones in my life.

I tell these stories with humility, and with great appreciation for how fortunate I’ve been. I’m thankful to God, and my family, for their support. I’m thankful for all the people who took the time to help me along the way. And I’m also grateful to soccer, the most beautiful of games, for taking a tiny kid named Edson, and letting him live the life of “Pelé.”

EDSON ARANTES DO NASCIMENTO

“PELÉ”

SANTOS, BRAZIL

SEPTEMBER 2013

BRAZIL, 1950

1

“Goooooooooallllllllllll!!!!!!!!”

We laughed. We screamed. We jumped up and down. All of us, my whole family, gathered in our little house. Just like every other family, all across Brazil.

Three hundred miles away, before a raucous home crowd in Rio de Janeiro, mighty Brazil was battling tiny Uruguay in the final game of the World Cup. Our team was favored. Our moment had come. And in the second minute of the second half, one of our forwards, Friaça, shook off a defender and sent

a low, sharply struck ball bouncing toward goal. Past the goalie, and into the net it went.

Brazil 1, Uruguay 0.

It was beautiful—even if we couldn’t see it with our own eyes. There was no TV in our small city. In fact, the first broadcasts ever in Brazil were occurring during that very World Cup—but only in Rio. So for us, as for most Brazilians, there was just the radio. Our family had a giant set, square with round knobs and a V-shaped antenna, standing in the corner of our main room, which we were now dancing around madly, whooping and hollering.

I was nine years old, but I will never forget that feeling: the euphoria, the pride, the idea that two of my greatest loves—soccer and Brazil—were now united in victory, the best in the entire world. I remember my mother, her easy smile. And my father, my hero, so restless during those years, so frustrated by his own broken soccer dreams—suddenly very young again, embracing his friends, overcome with happiness.

It would last for exactly nineteen minutes.

I, like millions of other Brazilians, had yet to learn one of life’s hard lessons—in life, as in soccer, nothing is certain until the final whistle blows.

Ah, but how could we have known this? We were young people, playing a young game, in a young nation.

Our journey was only beginning.

2

Prior to that day—July 16, 1950, a date that every Brazilian remembers, like the death of a loved one—it was hard to imagine anything capable of bringing our country together.

Brazilians were separated by so many things back then—our country’s enormous size was one of them. Our little city of Baurú, high on a plateau in the interior of São Paulo state, seemed a world away from the glamorous, beachside capital in Rio where the last game of the World Cup was taking place. Rio was all samba, tropical heat and girls in bikinis—what most outsiders imagine when they think of Brazil. Baurú, by contrast, was so cold on the day of the game that Mom decided to fire up the stove in our kitchen—an extravagance, but one she hoped would help heat up the living room and keep our guests from freezing to death.

If we felt distant from Rio on that day, I can only imagine how my fellow Brazilians in the Amazon, or in the vast Pantanal swamp, or on the rocky, arid sertão of the northeast, must have felt. Brazil is bigger than the continental United States, and it felt even bigger back then. This was a time when only the fabulously wealthy could afford cars, and there were hardly any paved roads in Brazil to drive them on anyway. Seeing anything outside your hometown was a distant dream for all but a lucky few; I would be fifteen before I ever saw the ocean, much less a girl in a bikini!

In truth, though, it wasn’t just geography that was keeping us apart. Brazil, a bountiful place in many ways, blessed with gold and oil and coffee and a million other gifts, could often seem like two completely different countries. The tycoons and politicians in Rio had their Paris-style mansions, their horse-racing tracks, and their beach vacations. But that year, 1950, when Brazil hosted the World Cup for the first time, roughly half of Brazilians usually didn’t get enough to eat. Just one in three knew how to read properly. My brother and sister and I were among the half of the population who usually went barefoot. This inequality was rooted in our politics, our culture, and our history—I was a member of just the third generation of my family born free.

Many years later, after my playing career was over, I met the great Nelson Mandela. Of all the people I’ve had the privilege of meeting—popes, presidents, kings, Hollywood stars—no one impressed me more. Mandela said: “Pelé, here in South Africa, we have many different people, speaking many different languages. There in Brazil, you have so much wealth, and only one language, Portuguese. So why is your country not rich? Why is your country not united?”

I had no answer for him then, and I have no perfect answer now. But in my life, in my seventy-three years, I have seen progress. And I know when I believe it began.

Yes, people can curse July 16, 1950, all they want. I understand; I’ve done it myself! But it was, in my mind, the day Brazilians began our long journey down the road to greater unity. The day when our whole country gathered around the radio, celebrated together, and suffered together, as one nation, for the very first time.

The day we began to see the true power of soccer.

3

My earliest memories of soccer are of pickup games on our street, weaving through small brick houses and potholed dirt roads, scoring goals and laughing like crazy between gasps of cold, heavy air. We would play for hours, until our feet hurt, and the sun went down, and our mothers called us back inside. No fancy gear, no expensive jerseys. Just a ball—or something like it. Therein lies much of the beauty of the game.

As for what I did with that ball . . . well, I learned almost everything I know from my father, João Ramos do Nascimento. Like virtually everyone in Brazil, he was known by his nickname—Dondinho.

Dondinho was from a small town in the state of Minas Gerais, literally “General Mines,” where much of Brazil’s gold was found during colonial times. When Dondinho met my mother, Celeste, he was still performing his mandatory military service. She was in school at the time. They married when she was just fifteen; by sixteen she was pregnant with me. They gave me the name “Edson”—after Thomas Edison, because when I was born in 1940, the electric lightbulb had only recently come to their town. They were so impressed that they wanted to pay homage to its inventor. It turned out they missed a letter—but I’ve always loved the name anyway.

Dondinho took his soldiering seriously, but soccer was his true passion. He was six feet tall, huge for Brazil, especially in those days, and very skilled with the ball. He had a particular talent for jumping high into the air and scoring goals with his head, something he once did an amazing five times in one game. That probably was—and is—a national record. Years later, people would say, with some exaggeration—the only goal-scoring record in Brazil that doesn’t belong to Pelé is held by his own father!

It was no coincidence. I’m certain that Dondinho could have been one of the all-time Brazilian greats. He just never got a chance to prove it.

When I was born, my dad was playing semiprofessional ball in a town in Minas Gerais called Três Corações—“Three Hearts,” in English. Truth be told, it wasn’t much of a living. While a few elite soccer clubs paid decent salaries back then, the vast majority didn’t. So being a soccer player carried a certain stigma—it was like being a dancer, or an artist, or any profession that people pursue out of love, not because there’s any real money in it. Our young family drifted from town to town, always in search of the next paycheck. At one point, we spent a whole year living in a hotel—but not quite the luxury kind, let’s say. It was, as we later joked, a zero-star resort for soccer players—as well as traveling salesmen and outright bums.

Right before my second birthday, in 1942, it looked like all that sacrifice would finally pay off. Dondinho got what appeared to be his big break. He was called up to play for Atlético Mineiro, the biggest and richest club in all of Minas Gerais. This was, finally, a soccer job that could support all of our family, maybe comfortably. My dad was just twenty-five; he had his whole playing career in front of him. But during his very first match, against São Cristóvão, a team from Rio, disaster struck when Dondinho collided at full speed with an opposing defender named Augusto.

That was not the last we heard of Augusto, who would recover and go on to other things. But it was, sadly, the high point of Dondinho’s playing career. He catastrophically damaged his knee—the ligaments, perhaps the meniscus. I say “perhaps” because there were no MRIs back then, no real sports medicine to speak of at all in Brazil, in fact. We didn’t really know what was wrong, much less how to treat it. All we knew was to put ice on whatever hurt, elevate it, and hope for the best. Needless to say, Dondinho’s knee would never fully heal.

Unable to make it on the field for his second game, Dondinho was quic

kly cut from the team and sent back home to Três Corações. Thus began the true journeyman years, a period that would see our family constantly struggling to make ends meet.

Even in the best of times, things had been tough—but now Dondinho was around the house a lot, trying to stay off his knee, hoping it would somehow mend and he could go back to Atlético, or someplace similarly lucrative. I do understand why he did this; he thought it was the best path to making a good living for his family. But when he wasn’t well enough to play, there was hardly any money coming in, and of course there was no social safety net whatsoever in Brazil during the 1940s. Meanwhile, there were new mouths to feed—my brother and sister, Jair and Maria Lucia, had just come into the world. My father’s mother, Dona Ambrosina, also moved in with us—as did my mother’s brother, Uncle Jorge.

My siblings and I wore secondhand clothes, sometimes stitched from sacks used to transport wheat. There was no money for shoes. On some days, the only meal Mom could make us was bread with a slice of banana, perhaps supplemented by sacks of rice and beans that Uncle Jorge brought from his job at a general store. Now, this made us lucky compared to a great many Brazilians—I have to say that we never went hungry. Our house was of a decent size, not part of a slum—or favela, to use the Brazilian word—by any means. But the roof leaked, and water would soak our floor with every storm. And there was also that constant anxiety, which we all felt, including the kids, about where our next meal would come from. Anybody who has ever been that poor will tell you that uncertainty, that fear, once it enters your bones, it’s like a chill that never leaves you. To be honest, I sometimes feel it even today.

Our fortunes improved slightly when we moved to Baurú. Dad got a job working at the Casa Lusitania—the general store, which belonged to the same man who owned the Baurú Athletic Club, or BAC, one of two semiprofessional soccer teams in the city. Dondinho was an errand boy during the week, making and serving coffee, helping deliver mail and such. On weekends, he was BAC’s star striker.

Why Soccer Matters

Why Soccer Matters